Climate Change and Well-being: Building Resilience Through Social Connectedness

By Monica DeVidi Almost every day news breaks of another climate emergency occurring somewhere in the world. Hurricanes, forest fires, flooding, drought and extreme heat events are becoming more frequent and severe and are having a devastating impact on communities across the province. These events undoubtedly impact physical health through injury, disease, food and water…

By Monica DeVidi

Almost every day news breaks of another climate emergency occurring somewhere in the world. Hurricanes, forest fires, flooding, drought and extreme heat events are becoming more frequent and severe and are having a devastating impact on communities across the province.

These events undoubtedly impact physical health through injury, disease, food and water insecurity, smoke inhalation and heat stress (Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy, n.d.). While these physical health impacts are worrying, the mental health effects associated with climate change are expected to be among the highest health-related costs (Maguet et al., 2022). Climate anxiety/distress is the experience of being worried or concerned about how climate change will impact you, to the point where it beings impacting your life (Card, K., 2023). These feelings of distress are increasingly common, with vulnerable populations experiencing increased levels of mental, emotional and physical stress from natural disasters (Benevolenza & DeRigne, 2019). On March 30, 2023, BC Healthy Communities hosted a webinar on the topic of climate change and mental health and examined ways local and Indigenous governments can build resilience in their communities through improved social connectedness.

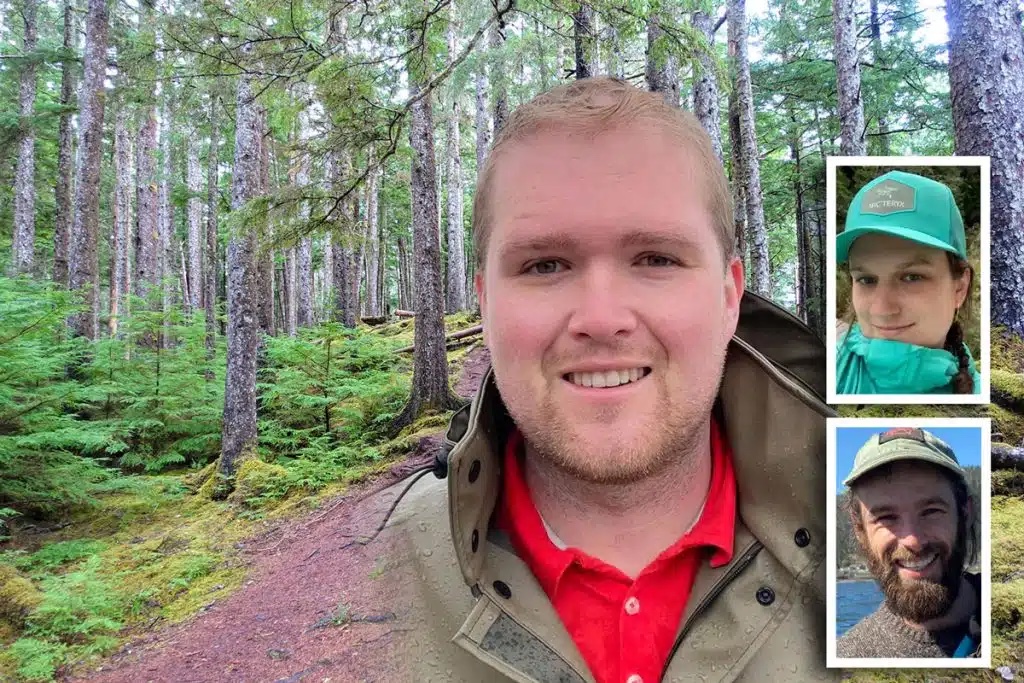

The webinar featured Dr. Kiffer Card, an Assistant Professor at Simon Fraser University in the Department of Health Sciences, who presented on climate-related ecological distress and resilience and shared findings from his team’s community-based evaluation of the mental health effects of climate change. We also heard from Caz Beaumont, Municipal Services Manager & Communications, and Jay Myers, Youth Program Manager, of the Village of Daajing Giids who spoke about their PlanH grant project which provided recreation opportunities for youth in their community—an incredibly important component of addressing climate anxiety.

Each of these speakers is addressing climate distress through different mechanisms, all necessary for long-term community empowerment and resilience. Here, we will discuss their work and how local and Indigenous governments can utilize the Research to take Action in their communities and create lasting change through the development of Healthy Public Policy.

Research ⇒ Action ⇒ Policy

Creating Healthy Public Policy is important for long-term solutions. Research conducted by academics such as Dr. Card, mental health experts and climate scientists helps identify problems, clarify the need for change and outline potential solutions. Individuals such as Myers and Beaumont, working on the ground in communities and developing programs for youth or others, produce an immediate impact on those people. The final step is to solidify those solutions in policy.

Step 1: Research

Dr. Card presented his research into understanding how people are being affected by climate change, particularly regarding their perceptions of preparedness to manage the challenging environments they face. Climate change is causing people to question their career paths, raise indecision over whether they should have children and instill anxiety over where they would go if their community was destroyed. He presented two definitions, one for Climate Distress, and the other for Climate Resilience, both developed with community advisor input.

Climate Distress can result in negative cognition (worry, stress, frustration, numbness etc.), functioning impairments (poor sleep, lack of motivation, reduced appetite, etc.) and social consequences (conflicts and disagreements). Climate Resilience focuses on how we can protect people from climate-related ecological distress. Interestingly, while distress-related factors focus on individual experiences with climate change, the climate resilience definition highlights both individual experiences as well the importance of sufficient community or societal-level resilience to really address the needs of people in the community. Strengthening social supports and promoting climate hope are important for mental health and sustained climate advocacy. It often takes a whole community approach to create conditions for all to thrive. Myers and Beaumont have developed a program that does just that.

Step 2: Action

The Village of Daajing Giids is a rural, remote, island-bound community on the far north coast of BC, on Haida Gwaii. The community is located entirely within 500 metres of the Pacific Ocean and faces significant climate adaptation now and into the future. This specific project was associated with the municipal-run Youth Centre, a space for youth to participate in recreation opportunities, build relationships and create community. Myers, the Youth Coordinator, planned four programs that address holistic health through land-based Haida cultural practices.

The programs were traditional drum making with a Haida elder, deer jerky processing, wild mushroom foraging and preservation and a Halloween dance. Myers shared how each of these programs taught the youth important skills, Haida cultural traditions, land-based connection, food sovereignty, self-sufficiency and provided an inclusive, safe environment for everyone to get to know each other and feel connected, especially important in the wake of COVID-19. The Youth Centre has partnered with Skidegate, a nearby Haida community, to share workshops and learn from each other. Myers also discussed the importance of Intergenerational programming, stating that we can all learn a lot from each other. Youth bring joy, lightness and inspiration, while Haida elders have a wealth of knowledge and wisdom, specifically around food gathering and processing. Individual mental health is typically better in socially connected communities and studies have shown that older adults in communities with stronger social cohesion fare better in natural disasters (American Psychological Society, 2021).

Building connections between community members are not the only important relationships to develop in order to improve climate resilience. Beaumont discussed the importance of building partnerships when creating policy. These partnerships can be with other municipalities, youth programs or organizations.

Watch our webinar about partnerships!

Step 3: Policy

Formalizing successful initiatives, such as the program in Daajing Giids, into policy takes time, extensive community engagement and political will. Many Local and Indigenous governments are working to develop policy that addresses the mental health impacts of climate change by providing opportunities for social connection, increasing access to greenspace, creating Emergency Response Plans informed by an equity lens, and providing effective disaster response services. As Dr. Card stated, it is important to “empower people to do things that are within their realm of control.” Individuals and communities alike must find where they can make an impact. While local mitigation efforts are important, municipalities cannot control greenhouse gas emissions for the entire planet. However, local and Indigenous governments are well placed to address the social determinants of health that are exacerbated by climate change.

BC Healthy Communities PlanH provides cash grants and capacity support to communities across the province towards creating and sustaining healthy public policies. BC Healthy Communities has provided Healthy Public Policy grants to communities across the province through our PlanH program. Working with local and Indigenous governments through PlanH enables them to find innovative ways to build climate resilience and address the mental health challenges they are experiencing in their communities. We are looking forward to seeing more innovative ways that communities will build climate resilience and address the mental health challenges experienced within their communities.

In case you missed it and want to learn more about climate distress and community resilience, a recording of our webinar can be viewed here: http://bchealthycommunities.ca/webinar-video-climate-change-and-well-bei…

Resources

American Psychological Association. (2021). Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Inequities, and Responses. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/mental-health-climate-change.pdf

Benevolenza, & DeRigne, L. (2019). The impact of climate change and natural disasters on vulnerable populations: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 29(2), 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2018.1527739

Maguet, S., McBride, S., Friesen, M., Takaro, T. (2022). Climate, Health and COVID-19 in British Columbia. Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions. https://pics.uvic.ca/sites/default/files/PICS_00621_Climate_Health_Covid_Report.pdf

Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy. (n.d.). Addressing Climate and Health Risks in BC: Communities. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/climate-change/adaptation/health/final_climate_and_health_backgrounder_communities.pdf